Originally published as a three-part interview in Rave-Up issues 8, 9 & 10

An edited version was published in the October 1994 issue of DISCoveries magazine

Interviews by Devorah Ostrov & Steve Hill/Story by Devorah OstrovAn edited version was published in the October 1994 issue of DISCoveries magazine

|

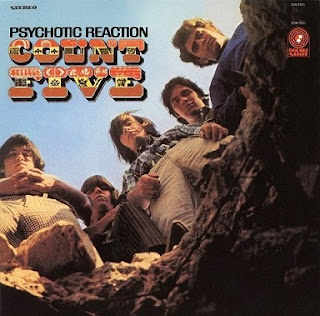

Count Five pose in front of San Jose's Winchester Mystery House

in this iconic publicity photo.

|

Here, the members of Count Five — vocalist/harmonica player Kenn Ellner, vocalist/rhythm guitarist John "Sean" Byrne, lead guitarist John "Mouse" Michalski, bassist Roy Chaney and drummer Craig "Butch" Atkinson — tell their story...

In the mid-'60s, San Jose, California, boasted one of the most happening music scenes in the country. Bands like the E-Types, the Stained Glass, the Chocolate Watchband, and the Golliwogs (they later changed their name to Creedence Clearwater Revival) were rivals and friends, but the undisputed kings of the turf were the British Invasion-inspired Count Five.

Michalski: We had San Jose wrapped up! Everybody was our fan. We got along with the kids really well, so we had a good following.

The band's beginnings, however, were less than auspicious. Like every other kid growing up in the '60s, each member of the group was infatuated with rock 'n' roll.

Byrne: I grew up with the Beatles. I wanted to be a musician, and I emulated the Beatles.

|

| Psychotic Reaction LP (Double Shot Records - 1966) |

Michalski: I used to listen to a lot of the Ventures. I picked up an acoustic guitar and just went by ear. I kept listening to the radio, trying to pick up everything people were playing. That's how I got going.

By 1964 Michalski and Chaney had formed an instrumental surf group with drummer Skip Cordell. In 1965, keyboardist Phil Evans joined, and when they decided to add a vocalist to the lineup, Ellner auditioned.

Ellner: I had been auditioning throughout the [Santa Clara] Valley with a bunch of groups, and I went over there. I knew Phil, we went to the same high school, and he had heard me sing. And I'd known Roy since I was eight years old; we were in elementary school together. They were operating out of somebody's living room. They really weren't playing anywhere.

|

Buffalo Springfield and Count Five

at the Third Eye - Redondo Beach, CA.

October 14/15, 1966

|

As their reputation grew, Evans was dumped.

Ellner: Things weren't working out with our piano player. He was having some problems with a girlfriend, and it was a real hassle hauling around this 100-pound piano. Roy and Mouse said, "I think it's time we get somebody new."

Byrne's family had left Dublin, Ireland, and settled in San Jose just a few months earlier, buying the house across the street from Ellner. Like the others, he attended Pioneer High.

Byrne: I came over and asked if I could play. Roy had a guitar I could use.

Ellner: We brought Sean in, and he was playing guitar and writing songs. We started changing our repertoire, and our prowess as the Squires started to get a little bit better.

Next to go was drummer Cordell.

More auditions yielded an English drummer named Larry.

|

| Count Five publicity photo |

At this point, the Squires became Count Five.

|

| Four-song EP issued on the French Disc'AZ label - 1966 |

Perpetuating the Dracula association, an early publicity photo showed them posed in front of San Jose's Winchester Mystery House draped in ankle-length black capes.

Ellner: That was mine and Sean's idea. We came up with the capes and ruffled shirts.

Byrne: It just fit. We thought that capes went with Counts.

But the capes turned out to be stifling onstage costumes.

Ellner: They were so hot, we'd only wear them for the first two or three songs. Then we'd take them off.

Byrne: It was accepted in Ireland by the time I left in 1964, but when I came to this country — look out! It was not accepted, and it caused me a lot of problems.

Michalski: I got kicked out of school for having long hair. In those days, it was just a little over my collar.

|

Count Five publicity photo

(from http://countfive.com)

|

Drummer Larry came and went quickly.

Ellner: Larry was with us for a couple of gigs, then he got real weird. I don't remember if he quit or if we fired him, but it got real bad and he left. Then my next-door neighbor told me about Butch, and I went over and talked to him.

Atkinson recalls an uneventful audition.

However, he actually made quite an impression on the band.

Ellner: There was this one song we'd written which had a very Byrds-type feel to it. Butch came in, sat down, and just played it. It kind of blew us away that he knew our song! He thought it was one of the Byrds' tunes, so he was playing it in this sort of Byrds/Mike Clarke-style. Plus, his drums were red!

At this early stage, the group rehearsed at Atkinson's house.

Atkinson: We practiced in my living room. My mom still has ringing in her ears 20 years later!

|

Count Five with Iron Butterfly and

Bystanders - Santa Rosa Fairgrounds

May 13, 1967

|

Michalski: They said, "Go for it!"

Chaney: They were behind us all the way.

Regular work was still hard to come by, and the group almost broke-up before it had even started.

Ellner: We had only played a couple of dates, and we hadn't gotten a job in about a month and a half. It was kind of slow, and we were getting on each other's nerves. Mouse and Roy came over one night and said, "That's it, we're not going to play anymore. We're going to quit."

Minutes later, they were offered their breakthrough gig.

Byrne: It was a tremendous club for teenagers! We were so big at the Cinnamon Tree, they did a full-length painting of us on the wall — with our capes. That was our regular club, maybe the most regular we ever played at.

|

| Count Five publicity photo |

Ellner: The San Jose scene was incredible! I have yet to see a scene like that anywhere else. There was a great rivalry and a great camaraderie between the groups.

Atkinson: That was probably the most fun of anything, the camaraderie we had with the other groups. We got along real well with the Syndicate of Sound. It just seemed that anybody you had music in common with was pretty easy to get along with.

Count Five rapidly gained a large local following, comprised of mostly teenage girls.

|

1967 Double Shot advert for singles

by Count Five & Brenton Wood |

And "Psychotic Reaction," at that point one of the band's few self-penned numbers, stood out as a crowd favorite. Although many were mistaken about its subject matter.

Ellner: Sean was in a psychology class with a friend of Butch's named Ron Lamb. They were talking about emotional problems, like neurotic and psychotic reactions, and Ron said, "God, that's a great name for a song!" Sean said, "You know, you're right!" So, Sean came back... I had just got my first harmonica and we were jamming, and we got into the part of the song that goes da/da/da/da/da... That's how the whole thing got started. Then Sean wrote the lyrics to it.

Ellner: He told us he was going to get us a recording deal in six months, and in a year we'd have a record in the charts — and that's exactly what happened!

|

Sons of Champlin and Count Five

at San Francisco's Carousel Ballroom

July 6, 1967

|

Chaney: He kept us straight in public. He was always telling us to watch our "P.I." or public image.

Michalski: He was like our chaperone, but he was cool! He was a cool guy.

And sometimes, it was handy to have someone's dad around.

Michalski: It's like everybody would be harassing us, and he would take care of us a lot of times.

Ellner: One time, we were walking through the Pittsburgh Airport on our way to catch a plane, and one of the ticket takers made a remark about us being faggots. My dad had had enough of it because we got it everywhere we went. My dad went over and said, "Okay, big man..." They got into this big fight over it. They had to pull my dad away from him!

When Count Five played at West Valley College in San Jose, Ellner's father befriended influential KLIV disc jockey Brian Lord. The DJ asked if they wanted to play on the Dave Clark Five show the following month.

Atkinson: You know how we responded to that!

Atkinson: You know how we responded to that!

Ellner: [Brian Lord] went on the radio the next Monday and talked about us for 20 minutes, which really boosted our career.

|

| Count Five publicity photo |

Ellner: I got carried away and threw my cape to the audience, so we were short a cape. And that was the end of it.

Lord also arranged an audition for the band with the newly formed, LA-based label Double Shot Records.

Byrne: He's the one who got us the recording contract. We had been turned down by five other companies.

|

"Psychotic Reaction" b/w "They're Gonna Get You"

issued by Germany's Hansa label - 1966

|

Michalski: When we auditioned for Double Shot, they said "Psychotic Reaction" was the one they wanted — "We'll sign you guys right up!"

Ellner: There was a point where they didn't know whether to go with "Psychotic Reaction" or "They're Gonna Get You" for the A-side, because the requests were equal.

Byrne: To let you in on a little trivia, "They're Gonna Get You" was originally called "House on the Hill," but Hal Winn [the group's producer] didn't like it, so he changed it.

Some band members were sure that "Psychotic Reaction" would be a smash...

Ellner: I never doubted it for a minute. We were so naïve! "We're gonna make a record, and it's gonna be a hit!" And it was.

|

Count Five, New Dawn, and the

Art Collection at the Terrace Room

in San Jose — July 15, 1967

|

Michalski: I didn't think it would do that well. I thought it was a pretty simple song.

Ellner: Mouse and Roy hated it! They were into R&B and blues. We had some fights when it first came out because my father insisted that we play it twice a night, the first song of the set and the last song of the set.

As the single raced up the charts (eventually peaking at #5), the label pressed the group to quickly record a full-length album.

Byrne: "Psychotic Reaction" took off so fast that Double Shot said, "You've got to get down here and do an album." Do an album of what? We had no music!

Michalski: We had some other originals, but they wanted a lot of material, and they did push us to get the record out. We were making the songs up in the hotel room.

Byrne: One time, we were sitting in our hotel room, and Mr. Ellner says, "They're coming over to listen to you guys. What songs have you got?" We didn't have anything. I said to the guys, "How 'bout this?" and I started playing these chords and singing, "Some nights I'm alone..." Hal comes in and I sing, "Some nights I'm alone..." He says, "Okay, I like it."

That spur-of-the-moment composition was ultimately called "The Morning After," and it became the B-side of Count Five's rarely seen second 45.

|

1966 ad for the Big Bam in Alabama with the

Beach Boys, Peter and Gordon, Lou Christie, Ian Whitcomb, the Hollies (and in tiny print at the bottom of the page) Count Five. |

But disillusion with the recording industry soon set in.

Byrne: Our problems were with the engineer, the arranger, and the producer. At the time, we thought they didn't know their ass from a hole in the ground. We were told, "You don't know your own music." We were playing it, but they were telling us, "You don't know your own music."

Chaney: That's where they had more control. They figured they knew more about what people wanted to hear than we did. [The album] might have been different if it were done our way.

Michalski: They couldn't handle loud music and feedback. We'd get down there in the speakers and get the feedback — controlled feedback. They couldn't handle that. They'd say, "Hey, cut! Turn it down!" And I know I played better than what was on the album.

Ellner: We were rushed in the studio. Their whole thing was money. "That's good enough," was always the statement. We were never happy with any of the stuff, but they didn't care.

Atkinson: A lot of stuff we put on record didn't really work out. It kind of came out trashed. They didn't really work with us very much. I was so disappointed in the record at first because I thought they'd done such a terrible job of engineering it.

During one recording session, Ellner snapped.

|

| Pye International ad for "Psychotic Reaction" |

Ellner: And then I flipped them off. This guy [Hal Winn] was changing every f**king thing we did. He hated my voice, and he hated me. I was saying, "You can't do that. That's not our sound." The whole day he'd been cutting up everything we were doing, and I just couldn't take it anymore.

|

Count Five and E-Types at the Bold Knight

in Sunnyvale, California — July 7, 1967

|

Byrne: It was a song I came up with to fill the album. I had those words floating in the back of my mind. That song happens to have a mistake at the end of it. I was supposed to sing "big, big mouth" with the music, but I was one step late. We said, "Let's do it again," and they said, "You don't know what you're talking about." So, we left it in. It does sound pretty good.

And "Peace of Mind"...

Byrne: I remember that day very well because someone was singing off-key. If you listen real close, you can hear it. Thank God they blamed somebody else! It was me! Also, if you listen, you can hear the foot-pedal squeaking at the beginning of the song.

Atkinson: I forgot my WD40 that day. There are so many things they left in that album.

And what about "The World"...

Byrne: They didn't record the vocals as I was doing them, but Hal heard me and liked what I was doing. I sang it again and Hal said, "No, Sean, do it the way you did it the first time." So, I did it again and Hal says, "No, do it like the first time." It got to be "The World," take 15! I was going out of my mind trying to remember what I had sung. I don't remember what take they used; I did it so many times.

|

Black & white publicity pic of the LP cover

(from http://countfive.com)

|

Ellner: When we did "Psychotic Reaction," he didn't really do anything; he just sat there. I don't even consider him as producing "Psychotic Reaction." All we did was go in to do a demo tape. They turned on the machine and that was it. I think they probably cut it flat.

And the much-noted "phasing" effect you hear on the song wasn't an added production feature but a technical glitch.

Ellner: They took the mono mix and popped it onto another track to make it double-track stereo, and because of that, you get a lot of cancellations going on. That's what's happening, you're canceling lots of notes and it sounds like crap! It's not a true phase shifter.

They do, however, acknowledge the wisdom of some changes Winn made to their signature tune. He suggested that Byrne insert the classic tagline: "And it feels like this!" And it was Winn's idea to shorten the song by an entire verse.

Ellner: Those were his two production moments. Originally, there was an additional verse at the end. After, "I can't get your love/I can't get satisfaction/Uh-oh, little girl/Psychotic reaction," we modulated the key, "Da, da, da, da duh..." and went into the final verse. Hal cut the modulation, went back into the centerpiece, and then faded out because the song was too long. That was smart. Given the market at the time, I think it was a good move.

|

Four-song EP issued on Mexico's Gamma label - 1966

|

While much has been written about Count Five being "San Jose's answer to the Yardbirds," it's interesting that the album's two covers — "My Generation" and "Out in the Street" — are both from the Who's catalog.

Byrne: At the time, we did more Yardbirds' covers than we did Who. The only reason the Who songs appear on the album is because we did them a little better than we did the Yardbirds', at least as far as the record company was concerned. Truth is, we did neither of them very good.

Still, it was incredibly prescient of them to record "My Generation" before it became a hit for the Who in the US.

Byrne: I have to give credit to Kenn and Mouse for that. They were always searching for new material to do, and at the time, Kenn was very into the "English Sound."

"Psychotic Reaction" began its climb up the charts during the summer of 1966, and by September, the guys were on the road full-time promoting it.

|

| Count Five hanging out with the Voxmobile in 1967! |

One memorable bill had Count Five topping the Doors!

Michalski: I remember the first time I met Jim Morrison. He said, "The only difference between my group and your group is that you've got a hit record." He had mustard all over his face from eating a hot dog! He was a pretty sloppy guy.

|

Casey Kasem interviews Count Five on Shebang, 1966

(from http://countfive.com) |

The band's most extraordinary experience, all agree, was playing a two-day festival known as the "Big Bam in Alabama."

Atkinson: That was our first big show!

Ellner: Alabama was amazing! That should have been one of our last tour dates because you should never start the first tour of your life like that.

|

"Teenie Bopper, Teenie Bopper" b/w

"You Must Believe Me"

Released on the Belgium Palette label - 1967

(Both songs were non-album tracks.)

|

Chaney: [The groups] rented the whole top floor of the hotel. We were playing poker with the Hollies; we were in the Hollies' room with the Beach Boys! And there's hundreds of girls outside banging on the door. Finally, Allan Clarke [of the Hollies] opened the door and said, "If you f**k, come in. If you don't, piss off!"

However, touring the Southern states in the 1960s presented some challenges as well.

Michalski: We had a lot of problems! We got into a lot of fights! Especially in restaurants. They'd call us hippies and queers and tell us to get out.

|

Count Five pose in front of the KCOP-TV van in LA.

(from http://countfive.com)

|

Count Five's Top 10 status guaranteed them appearances on all the local teen-oriented radio and TV shows across the country. But they missed out on two of the nation's biggest variety shows.

Ellner: And we turned down The Milton Berle Show. It was the first time a rock group was going to perform on the show. Milton Berle was intrigued by the capes and he wanted to include us in a skit, but nobody would take off school for a week to do it.

One TV show they did do was American Bandstand. After playing their hit, Dick Clark asked Ellner to explain their album cover.

|

Count Five publicity photo

(from http://countfive.com)

|

A second 45 — "Peace of Mind" b/w "The Morning After" — was released as the follow-up to "Psychotic Reaction," but by then, Double Shot had lost interest.

Double Shot issued a few more Count Five singles between 1967-1969, including several non-album tracks and a cover of Curtis Mayfield's "You Must Believe Me," none of which dented the charts.

Byrne: Our record company didn't promote us after "Psychotic Reaction." The dollars started rolling in for those guys, and they wanted to keep them. They didn't put the money into producing or promoting us.

|

"Reaccion Psicopatica" b/w "Te Encerraran"

("Psychotic Reaction" b/w "They're Gonna Get You")

issued on Spain's Hispavox label - 1966

|

Do they think that Double Shot ripped them off?

Atkinson: I'm sure the record company cut themselves a pretty good deal, but I'm sure it was all legal. We were all underage. We had to talk our parents into letting us sign the contracts, and they didn't know anything about the music business.

Chaney: Everyone seemed to be taking care of us, but I'm sure they were taking care of themselves too.

By 1968, Count Five was drifting apart. Michalski and Chaney were the first to leave. They were replaced by two members from the Syndicate of Sound for some local gigs. But by the end of the year, the band had broken-up.

|

The John Byrne Tribute to Bay Area Garage Bands

featuring Count Five, Syndicate of Sound & members

of the Chocolate Watchband - February 21, 2009

|

Michalski: And the draft got us. We were all 19, and at that time, when you were 19, you were drafted. Butch enlisted because he wanted to be a pilot. Sean wasn't a citizen yet, so he didn't have to worry. Kenn had a bad back. Roy got out of it. But it took me four years to beat it.

Ellner would have liked to have carried on a while longer.

Ellner: I really wish we had. I think all our lives would be quite different now.

One long circulated rumor has it that towards the end of the group's career, they turned down a million-dollar deal and instead went to college. Is that true?

Byrne: Yes! I'm sorry I didn't save the newspaper. The San Jose Mercury News had a front-page headline saying we turned down a million dollars. We turned down a tour; it wasn't a guarantee. Somebody said, "Your potential is a million dollars." But we did turn it down, and I was the cause of it because, believe it or not, I wouldn't quit college. I was having too much fun!

* * *

* John "Sean" Byrne died on December 15, 2008, from cirrhosis of the liver.

* Craig "Butch" Atkinson passed away on October 13, 1998.

* For more information about Count Five, visit the band's official website at http://countfive.com/about

Great stuff! I'm following.

ReplyDeleteThanks!

Delete